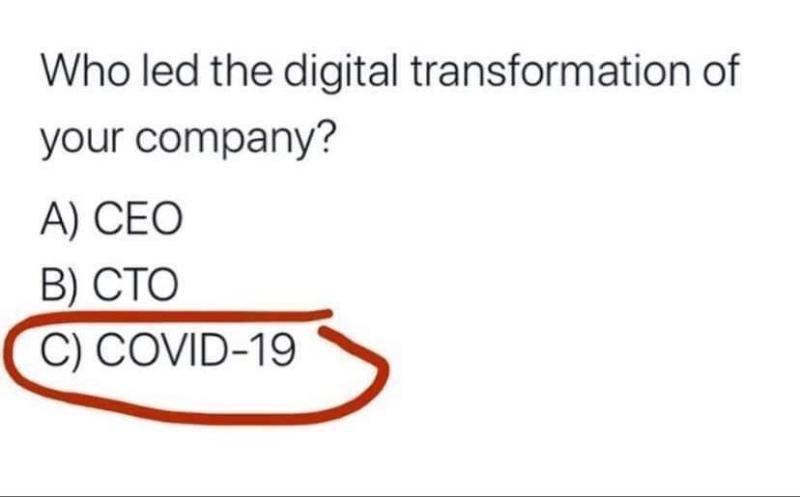

The last few weeks have seen rapid and quite astonishing changes in organisations all around us. Sleepy, slow-moving giants have made changes to their organisational structures and processes in a matter of days where previously they have struggled to make minimal progress over multiple years. Similarly, companies who have spent years jealously guarding percentage points of market share have found themselves with common ground and collaborating with erstwhile rivals in ways that would have been unimaginable a few months ago.

Not only have these huge changes happened at a corporate level but individual employees are making changes to their behaviours, working practices, integration with technology and overall lifestyles that in the past would have probably been the product of huge, costly and multi-year corporate change programmes that delivered only limited success. Now all has, seemingly, been done in the blink of an eye with little or no friction or resistance.

What, if anything, can the change management community and theoreticians learn from what has happened? Here, one of us (Adam) must declare an interest. As a professional change management consultant for several decades, he has spent many years advising the Boards and Senior Execs of his clients to think through change carefully and to adopt all the aspects of best practice such as, for example:

- Crafting a properly articulated vision of the change that will explain why this change is needed and raises enthusiasm and energy for it

- Adopting fully the role of a Leader of the change – modelling the way and using your power to reward and admonish to bring about the change you want

- Having properly defined milestones and project plans

- Doing careful Stakeholder analysis and developing and engagement plan

- Reviewing key performance indicators rewards and incentives to discourage old behaviours and inculcate and sustain the new behaviours necessary to support change

- Redesigning organisations to support new systems, processes and responsibilities

- Creating communications programs to ensure employees understand the changes, why they are necessary and what they now need to do in relation to the changes

The list is endless and will be familiar to all practitioners in this field. And yet . . . in the space of a few short weeks profound change has occurred at a speed that clearly precludes much, if any, of this alleged best practice.

Does this mean that everything the change community has nailed firmly to its mast in past decades counts for nothing? On balance that would be too great a conclusion to draw from what has happened. Rather we think the current crisis brings into clear focus two things:

- The essential prerequisite of a compelling need for successful chance

- The need to rethink how change programmes are architected, planned and managed

Compelling need is not a difficult concept to grasp. Frequently referred to in the 1990s as the need for a “burning platform” or, more recently, “creating a sense of urgency” the argument goes that, for change to occur, those involved in it must genuinely believe that there is no alternative but to move from the status quo to a new way of doing things.

In the past few decades Adam has worked with clients and challenged them to articulate exactly why it is essential to their business that the changes they are proposing take place. This process of challenge – testing gut instinct and commercial intuition against rational analysis – helps executives to distinguish change that is truly essential from change that is a “nice to have” (or simply something that they quite like the idea of but have no real commitment to). Experience shows that changes that fall into the second and third categories have a tendency either to fail totally or to be implemented in an, at best, sub-optimal way.

The past few weeks have created a situation where a real compelling need to change has existed not just for the odd business here and there but for the entire economy (both profit and non-profit, public and private). The experience has surely confirmed just how much easier change is in the presence of a real imperative.

However, a note of caution should be introduced at this stage. Although compelling need forces change, in itself it is not going to be sufficient to keep organisations (or the behaviour of individuals) in their new state. Put simply, the pressures of the current situation have forced organisations to change and move to a new way of doing things. But now, unless people and organisations perceive this as a new and better way of doing things and, indeed, can think of improvements that could be made that would make things even better, there will be a powerful tendency to drift back to the old equilibrium once the current crisis is over.

We may have made massive changes in the space of a few short weeks but now is the time to be doing the hard work of thinking about all the other components of change (KPIs, rewards and incentives, involvement, behavioural plans et cetera) in the toolbox of successful permanent change if organisations are to make the most of this going forwards.

The Architecture of Change Programmes is another area where the current crisis has accelerated an existing trend. Historically, too many organisations have tried to make change happen via large multi-year change programmes. Typically, these involved such things as a programme office, detailed project plans, large, interdepartmental steering committees, and a superstructure (for want of a better word) of support functions. Such programmes assume a life of their own and have rarely delivered their expected benefits (it is astonishing how often and how eloquently senior executives post-rationalise failure as qualified success).

Covid-19 didn’t create the need to rethink this way of doing things but it has undoubtedly accelerated the trend and will continue to do so. For many years now it has become a cliché that we are living in a VUCA world (so much so that we hesitate to use the term here). The current crisis could not demonstrate this more clearly and large multi-year programmes simply won’t work in that environment. The world just isn’t staying stable enough to plan sensibly for multi-year change programmes. Instead smaller and more nimble ways of achieving change will be needed. The horizon has shrunk:what bite-sized change can be reasonably envisioned, constructed and implemented before the ground moves under your feet?

But this in turn will present a challenge to Leaders. They will need to be able to hold a vision of the overall future state they hope to achieve whilst being much more fluid about the precise steps and means by which they achieve it. Change will be achieved in fits and starts and the path will twist and turn under their feet. The adage of “plan what you can, don’t plan what you can’t” has never been more apposite. Many leaders will find this deeply uncomfortable. The days when they can set a grand vision and then think that they can just devolve the programme to others to deliver are over and, in truth those days never really existed for real change. Change now will be smaller, bite-sized and emergent (but no less radical for it).

Who we are:

Adam Gold founded Adam Gold Consulting in 2004. He has over 30 years’ experience in management consulting working at Board Level with private sector clients across Europe and Africa.

Adam can be contacted at: adamgold94@gmail.com

Christopher Lake is the co-founder of Syllogism, the recruitment, strategy, and ethics consultancy. A former fast stream civil servant, he was Tutor and Fellow in Politics at Magdalen College, Oxford from 1995 to 2000.

Christopher can be contacted at: christopher.lake@syllogism.co.uk